“Mannequin” is a mysterious hand-painted film by Ohio-based artist and animator, Pete Burkeet. Watch below, then check out our interview, where we’ll touch on Pete’s process as a solo animator, shooting ratios, and Andrew McCarthy’s greatest role.

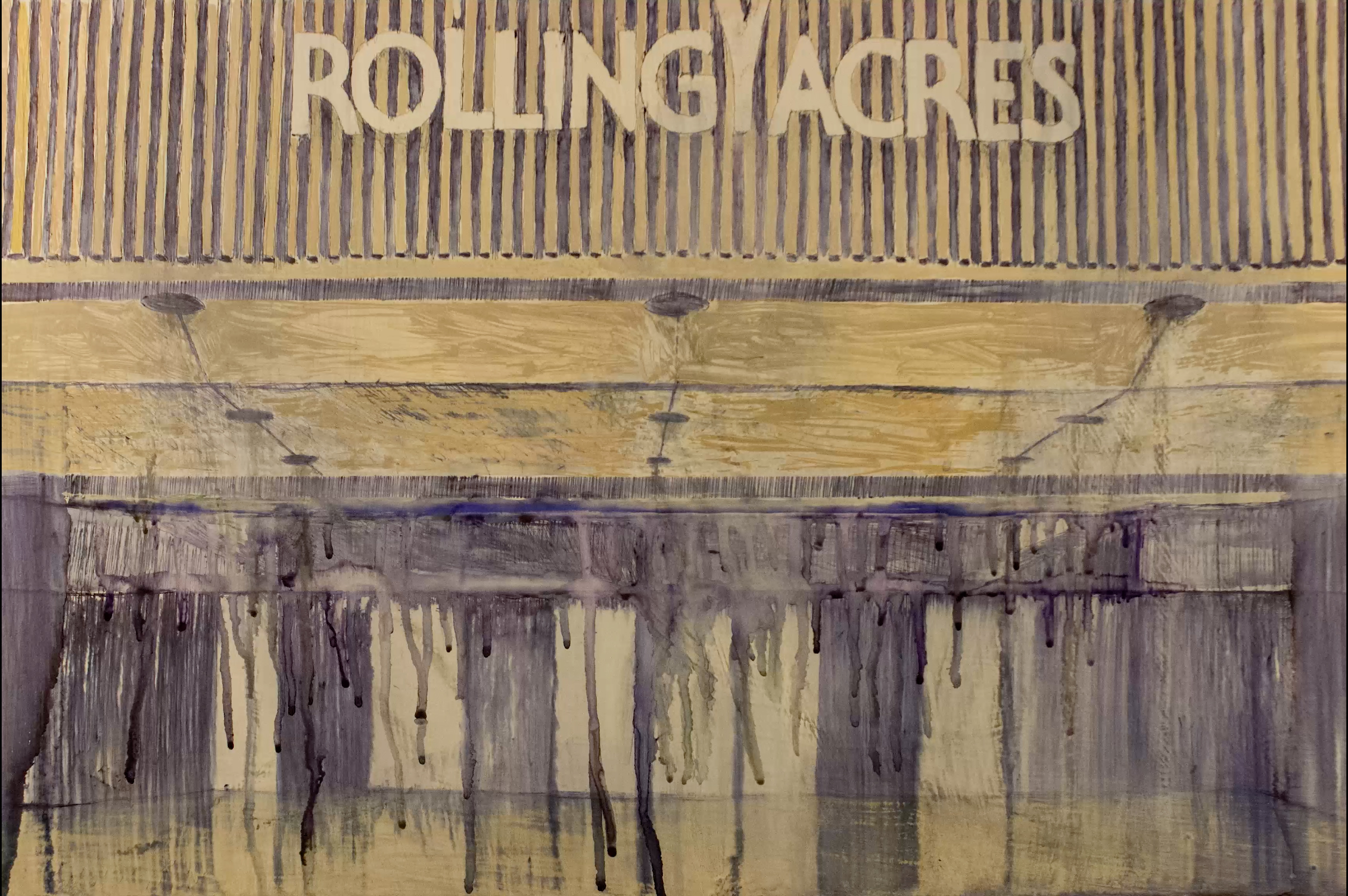

“Rolling Acres Mall was built on August 6, 1975. At its peak, it contained 140 stores. At one point, the mall was painted in pastels and was referred to as ‘The Plastic Palace.’ Rolling Acres began its decline in the 1990s and ultimately closed in 2011. It is now a magnet for crime and pollution.”

What was your personal connection to the Rolling Acres space, if any, and what made you want to make this film?

Growing up in the ‘80s meant going to malls a lot. I lived a bit closer to Canton [Ohio] so my family went there most of the time. We went to Rolling Acres a few times and I loved it because it was a more interesting looking mall than I was used to. In the ‘90s I began to develop a disdain for malls and what they represented, when they started their decline it barely interested me.

However, I have always been interested in spaces as representations of a mood or feeling. When the story of the Craigslist Killers happened in 2011 I looked into it and got the creeps / was fascinated. The killers were spotted all over the area I grew up and killed three men. I saw that they killed someone behind Rolling Acres and buried him in a shallow grave covered in lye. I immediately thought about how places with negative energy attract people with negative energy – about those places where moms always tell their kids never to go – for good reason.

I went to Rolling Acres with my girlfriend to take pictures of the grounds until security kicked us out. It was just as I suspected it would be, basically an illegal dumping site. Seeing it in person made me want to make something reflective of the kind of discarded space a dead mall represents and the kind of energy it could be brewing.

Can you talk a bit about the process of developing your initial idea, once you decided upon it?

The idea for “Mannequin” did not specifically come from Rolling Acres, for a minute I was thinking straight up working on a horror film. I was making paintings and had made a few short clips that were more of a meditation on evil but a few of the clips pushed me back into thinking about the space itself and how to express the energy of that space. I started getting into using mannequins as the inhabitants of the space and started drawing from pictures of discarded mannequins. As I was making clips I started hashing out a loose trajectory for the sequence to take and let it sort of mutate from there. A funny thing happened while shooting it. I half-watched the 80’s film Mannequin as I was working on one of the clips one night for research purposes, it was pretty meaningless at the time other than it was pretty standard 80’s fare and mildly entertaining. I showed my movie to a good friend when I finished it to see what he thought and he jokingly said I should make a trailer for it using Starship’s Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now (we have had a strange running Starship joke for years). I watched the video for that song and it was the featured song from the Mannequin soundtrack. Clearly important serendipity.

Ha. I haven’t seen Mannequin in years. Serendipitous indeed.

How long did it take you to make “Mannequin”? Did you begin the animation process knowing that the final project would have such a scale?

“Mannequin” began in fits and starts, the first clips were made over a year ago and I sat on them for a few months while I was making big paintings. I realized I had a few folders full of clips that started to resemble a seed of an idea and began to develop it. I make movies more like someone would make a painting, which means a lot of “sketches” were discarded on the way to the finished movie.

Your description of your process reminds me of a Louisiana Channel interview with David Shrigley where he defines “artwork” as the “residue of a process — of a project — rather than something you see and then have to realize, thereafter.” Defining “project” as “process” is healthy. “Project” as an exploration; finding the work, not the work itself.

Ok, so it seems you are understanding my world pretty well. I like the Shrigley quote a lot, it reminds me of seeing a Mark Bradford show and getting a kick out of his piece “Bag of Tricks” on the wall – it was a giant plastic bag full of the masking tape he used in his work.

I definitely respect movies/animations that have everything planned out meticulously and then execute those plans perfectly, I can’t imagine any animation that has been made for a studio done any other way. In my own work, I came to the conclusion a while ago that airtight planned and executed art leans toward architecture and art that seeks to establish and understand a layered process of experimentation leans toward music. In that way, I can appreciate films that are airtight on a superficial level but I rarely fall in love with them. I also think there is a lot to be said about truly understanding the medium one is using. For instance, David Lynch’s Eraserhead is clearly meant to be experienced in a theater with a great sound system and in its original print. He wanted to amplify the experience of seeing Film. Conversely, Guy Maddin who also developed his own personal vision for film using 8mm decided not too long ago to go digital and his creative vision lost a lot of its edge.

Making this film, were you ever lost along the way? How did you proceed?

In my own experimental animation work I have had a lot of “lost along the way” moments. They basically equate to a long-standing obsession with adding to my own bag of tricks and finding that sometimes that doesn’t work well with time-based work. That is what lead me to put “Mannequin” on the back burner for a bit and work on large scale still paintings, it’s also what lead to over half of what I ended up with on the cutting room floor. I actually got back into it with a few ideas of how I could connect the worlds I was working on in my mind, that gave me the drive I needed to not give a shit whether what I made was going to work or not.

The final movie was cut from animated clips that totaled over 20 min. I suppose it is a strange process. It began slow but between November and March I was working pretty much every day. If I get an idea for a clip or sequence that I think should be in the film I must make it happen. I often forget I how long I have been working but one time I realized I worked most of a 3-day stretch with very little sleep.

I love it. This pervasive idea that all animators do or should have a 1:1 shooting ratio is ridiculous. Leaving 13 minutes of full animation on the cutting room floor would give some people a panic attack.

The idea of not caring whether something I spent possibly 20 hours or more on was going to make the final cut is strictly a result of my years painting in Ohio. I have spent countless hours on paintings that have been seen by maybe 50 people and along the way painted over countless other ones I was not sold on. I think my process in animation is the bastard child of that masochistic process. Not to say that’s a bad way to do things, I think it’s the only way to do it. I was watching Charlie Rose interview Louis CK recently and Louis CK said a line about how writing comedy specials should be done in the way that they used to make samurai swords — that basically sums up how the art that I personally love is made. I love the idea that if you think you have an hour of material – no you don’t – write another hour and fold it into the first one. Same thing with music, every great album has b-sides that are good because of course they do… same thing with any art because you don’t develop a style without doing some serious weeding.

Hearing about diverse approaches gives me this complete feeling of relief. Have you read Laura Heit’s Animation Sketchbooks? It’s an anthology of sketchbook pages that gives you a glimpse into the thinking processes of dozens of independent animators. We’re taught that creating animation requires holistic pre-visualization. Storyboard, animatic, rough animation, cleanup, ink and paint, and compositing follow in strict order. But that’s studio convention; it’s not how everyone actually works.

I haven’t read Animation Sketchbooks – that sounds interesting though. I like the idea of getting a whole lot of processes in one place like curating animation stylistically instead of by story genre.

I also never took a for real class in animation, so there’s that.

There’s so much texture to this film. What are the physical dimensions of the artwork, and what did your animation setup look like?

The dimensions for the individual shots vary but the largest is probably around 2ft by 21/2 ft. You can get a sense from my studio shots.

So are you shooting with a DSLR, saving the images on an SD card, and importing them all as image sequences for editing later?

Yeah, that’s exactly the process, lots of processing the clips after bringing them in, etc., but yeah.

Where did the overhead projector come into things?

The overhead is sort of my bag of tricks. I have never been interested in conventional drawing skills, I have toyed around with overheads for a long time trying to figure out strange ways of using them. I always loved overheads because of the level of detail they project and how when using one I don’t have to think about proportion at all and can focus more on material and color. There are a few experiments I did with shooting the projections themselves that ended up in the final export of “Mannequin”.

Can you share some influences on your visual style?

I have a lot of influences from painting, animation, sound, and film. A few of the painters I often look at are Francis Bacon, William Blake, Picasso, Mark Tansey, Cecily Brown, and Nicole Eisenmann. As far as animation goes I am drawn to anyone using unconventional techniques, I like William Kentridge, Adam Beckett, Don Hertzfeldt, Roland Topor and Rene Laloux’s Le Escargots/ Fantastic Planet, and Asparagus by Suzan Pitt. I am also influenced by certain moments in films, individual films, and the styles of certain directors. The opening scene to Touch of Evil deals with time in ways that I am still trying to figure out. I can watch Guy Maddin’s Heart of the World over and over. Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal is still one of my favorite films. and I am a huge fan of David Lynch’s ideas and how he fits them together, especially in Eraserhead and Mulholland Dr.

Big thanks to Pete for giving us a look into his process. Check out his website to explore his entire body of work, including paintings, collage, installations, GIFs, animated films and music videos.

DIY Animation Club co-founder Dave Merson Hess taught and developed animation curriculum for Aurora Picture Show’s youth workshops, 2014-2018. He also started Rush Process, a Gulf Coast-based festival celebrating animators who work with physical media, which ran from 2015 to 2018. Dave is currently an MFA candidate in Experimental Animation at Calarts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.